Old consoles fail, arcade cabinets die, computer systems become outmoded, and even emulators need to be updated. We need to find a reliable way to keep games not just alive, but interactive. (After all, what is a game without a player?)

Learning from the past

Gamers seeking respect for our medium often compare video games to films, and there are some clear parallels: films, like video games, took a long time to gain respect from the cultural elites of America, even while outpacing other media in this country. With this in mind, it’s important to remember the hard lessons learned from early film preservation, or rather the lack thereof.

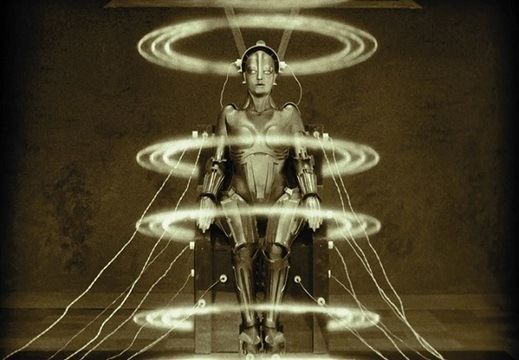

Color-tinted still from “Metropolis,” a big-budget, highly influential silent film that was partially lost for decades.

It’s estimated that 75-90% of all the silent films ever made have been lost forever, many of them discarded by the very companies that made them, believing the films were worthless, while others deteriorated because of the unstable film stock they were printed on. Rarely, a lost film resurfaces, usually in either a formal archive or a private film collection.

So what does that have to do with video games?

I’m not trying to be alarmist; video games have much better chances of surviving into the future than early films did, but only if we start taking action now. As difficult as it might be to believe, video games won’t last forever. We already have advantages that film never had: games are distributed on a much larger scale, and even the most delicate games are much more stable than early film stock.

But if people treat games as a disposable consumer product, those advantages won’t mean much.

What do we do?

Well, there seem to be several options. One is to rely on video game companies to re-release their old titles, though this only happens to a select few titles and comes with its own problems. We could also rely on museums and other institutions to add games to their collections, and hope that some of them offer the chance to replay these games. Other options include ROMs and emulators such as the Internet Archive’s Console Living Room. Or we could take care of our own games and hope for the best.

But even the best options aren’t foolproof, and unfortunately there seem to be a lot of thorny legal issues involved that are affecting even museums’ ability to properly preserve their collections.

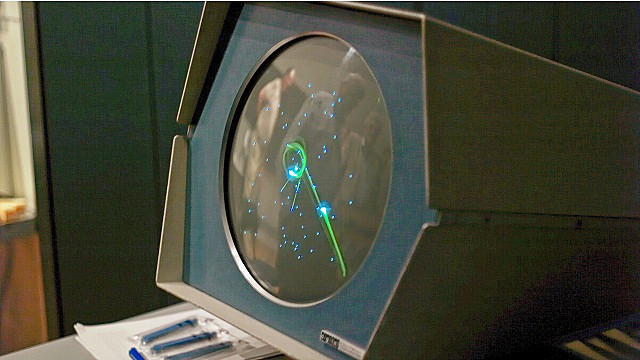

The Computerspielemuseum (Museum of Video Games) in Berlin has run into hardware and copyright issues when trying to keep its game collection viable.

If we hope for all examples of our medium to survive – both the famous and the infamous, the “classics” and the “cult classics” – it’s up to us as video game lovers to work to save what we can, so future generations can understand the history and significance of video games.

We need to support others’ efforts at preservation. We need to work with companies and lawmakers to untangle the copyright issues hindering attempts at preserving games. We need to work together as a community to save our history and treat our beloved medium with the respect it deserves.

We need to talk about video game preservation.